Published March 1st, 2023

Table of Contents:

- Introduction

- Method of data collection

- The difference between “client”-side and “vendor”-side workers

- Employer Sponsored Healthcare

- Employee Retirement Funds

- Lack of overtime protections

- Rest Periods and Meal Penalties

- Safety concerns in the workplace

- Training Opportunities

- Current industry wage distribution

- Are visual effects jobs sustainable?

- Key Survey Quotes

- Glossary

- Contact an Organizer

Introduction

Three years ago, a group of Visual Effects workers employed on film crews throughout the United States began setting up organic social networks to connect with their peers and discuss their working conditions. Since Visual Effects is among the only departments engaged in film and television production that does not have a collective bargaining agreement or union representation, these workers sought to fill the information void themselves. A survey was launched to try to source and publish information about wage rates and working conditions, which initially received hundreds of responses from VFX crew working directly for major studios. Launched on November 10, 2022 and conducted under the auspices of the entertainment crew union, the International Alliance of Theatrical Stage Employees (IATSE), this third iteration survey has grown to encompass workers across the entire VFX industry in the United States, Canada, and beyond.

While initially aimed at helping VFX workers advocate for themselves in negotiations by publicizing rate information that the producers who hire them are loath to share, the survey now additionally seeks to understand these workers’ shared challenges in building a sustainable career in VFX, as well as to highlight the stark contrast between the non-union VFX workers’ experiences and that of their unionized coworkers, who are often unaware that their colleagues are not offered the same benefits and protections as every other IATSE-represented craft on set.

The findings paint a picture of an industry in crisis. An overwhelming majority of VFX workers feel that their work is not sustainable in the long term. For VFX workers employed directly by film productions (and it is worth mentioning that the VFX department’s budget is generally the biggest single line-item of any production’s budget), only 12% have health insurance which carries over from job-to-job, and only 15% report any kind of employer contributions to a retirement fund. On average, 70% of VFX workers report having worked uncompensated overtime hours for their employer. Overall, 75% of VFX workers reported being forced to work through legally mandated meal breaks and rest periods without compensation. The majority of on-set VFX workers reported working in conditions they felt unsafe in. A further 75% of VFX workers employed by the major film studios had no access to any employer-provided training or educational resources. And across the industry, only about 1-in-10 VFX workers felt able to individually negotiate viable solutions to these challenges with their employer.

Method of data collection

We used an online form which required registration via email to ensure unique responses from individual workers. Workers were asked a variety of questions regarding their wages and working conditions. The survey ran for approximately 2 months and IATSE supported outreach and advertising through email and social media to help gain participation. Once the survey was concluded, worker volunteers have been engaged in an effort to contact all responders to verify the information provided and in some cases secure permission for their quotes to be published in this report.

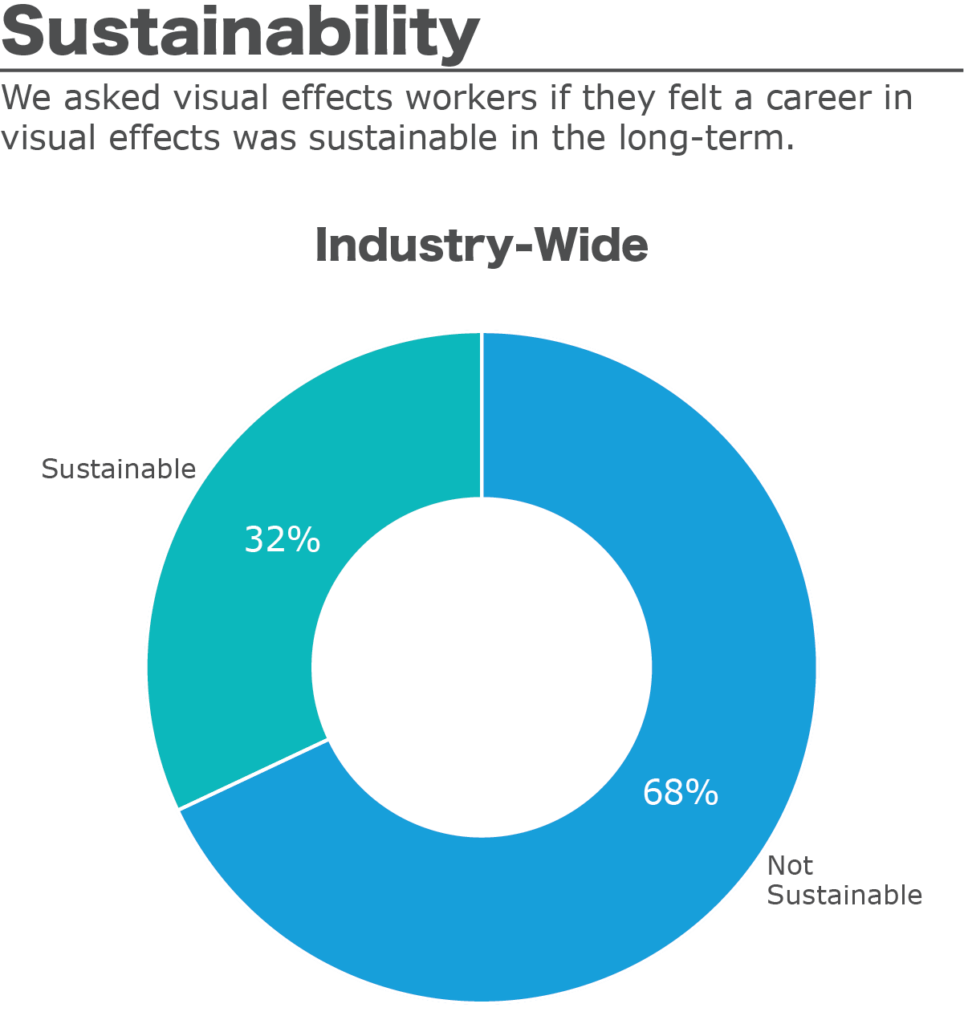

Extreme outliers or form entry errors were removed to harmonize the results. During parsing, any identifying information was removed and the aggregate data was compiled both in an industry-wide data set and broken down into client- and vendor-side sets, with a roughly even split among responders across these two sectors of the industry. In some cases when there was no statistically significant difference between the client- and vendor-side, as with the section on “Sustainability,” we have reunified the findings into an industry-wide result.

The difference between “client”-side and “vendor”-side workers

The Visual Effects industry is generally broken down into two separate groups of VFX workers, known as the “client” or “production”-side, and the “vendor”-side. Where applicable, we have separated the results based on whether a worker self-identified as working client-side or vendor-side, in order to reflect the differing experiences faced by these groups of workers.

The client-side workers are employed directly by the film production company (working under the direct supervision and control of the studio), and work alongside the rest of the IATSE-represented crafts (camera, editorial, art, etc.) in pre-production, on set, and in post. For these workers, Visual Effects is the only department on the film crew which has not yet been organized and which does not work under a collective bargaining agreement. Their main role is to execute the director’s creative vision for the visual effects on a film, by working with the filmmakers to create a plan for the VFX methodology, budget the show, hire vendors to do the art, and interface directly with the on-set teams, editorial, color, and the studio to iterate on the VFX work from earliest pre-vis to final delivery. Client-side VFX teams are typically among the first crewmembers to be hired after a movie has been green-lit, and are always the last standing as they continue to refine and perfect the look of the film after editorial has finished cutting.

The vendor-side workers are what most people outside the industry think of when they hear “VFX workers”; that is, they are employees of one of the hundreds of Visual Effects vendor houses which employ teams of artists, production staff, programmers, producers, and executives in order to bid on work being requested by a project. Typically the work is bid out on a shot-by-shot basis, but in recent years it has become commonplace to have vendors submit flat bids for the entire scope of work assumed to be required by a project going into production; this can lead to cases where vendors, already forced to undercut each other in order to secure a contract, are forced to exceed the budgets they had allocated for a show because of revisions or reconceptualizations demanded by the filmmakers. These workers typically do not work alongside union members and are often forced into a transient lifestyle, as their employers chase government tax subsidies and open new branches (sometimes only for the length of one project). Depending on the job title, they may be long-time employees of a company, or may be freelancers like the client-side workers, only hired for a period of months before being let go once work on a show has completed. These workers receive footage, concept art, previs, and direction from the client-side VFX teams, and pass back iterations of the VFX work over the course of months or years in order to achieve a finished product.

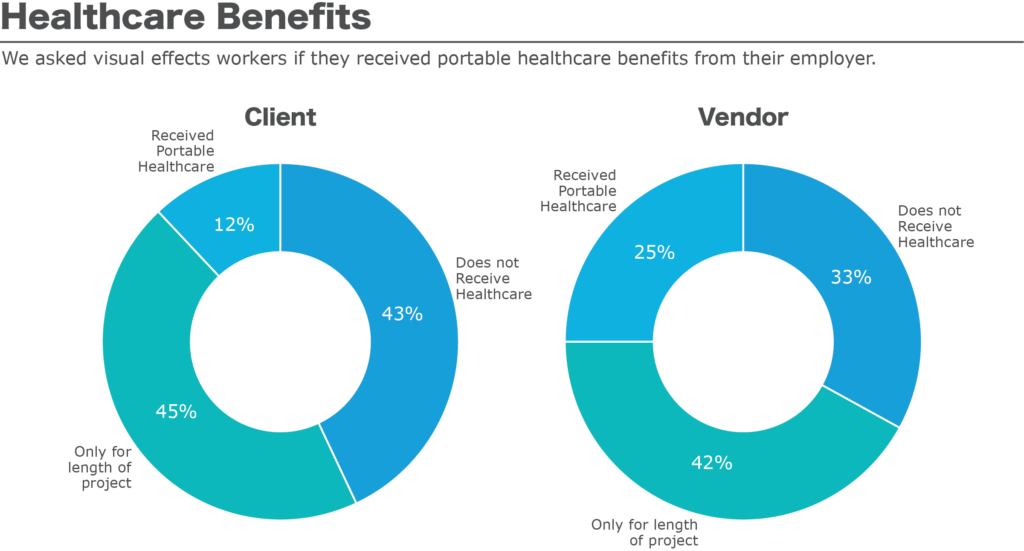

Employer Sponsored Healthcare

Members of IATSE-represented departments, who work directly with client-side VFX workers for the same employers and in the same conditions, have almost universally benefited for decades from inclusion in union-negotiated healthcare coverage (such as those provided by the Motion Picture Industry Pension and Health Plans and the National Benefit Funds), or a comparable plan for those covered by DGA or WGA agreements. However the breakdown we see here is stark; for client-side workers, only 12% responded that they have portable healthcare which travels from job-to-job with them. The vast majority of these workers are on their own to pay for healthcare for themselves and their families, even if they are classified as full-time employees of a production company producing a film over the course of years.

Vendor-side workers see little improvement on this, with only 25% saying they have a health plan which they can keep from job-to-job.

Considering the well-known stressors which persist across all aspects of entertainment work, especially on major motion pictures, the toll this lack of healthcare support from employers takes on workers is formidable. When we asked workers whether or not they feel their work in VFX is sustainable long-term, the majority of respondents answered “No” and listed the lack of healthcare benefits as a major contributing factor to their burnout.

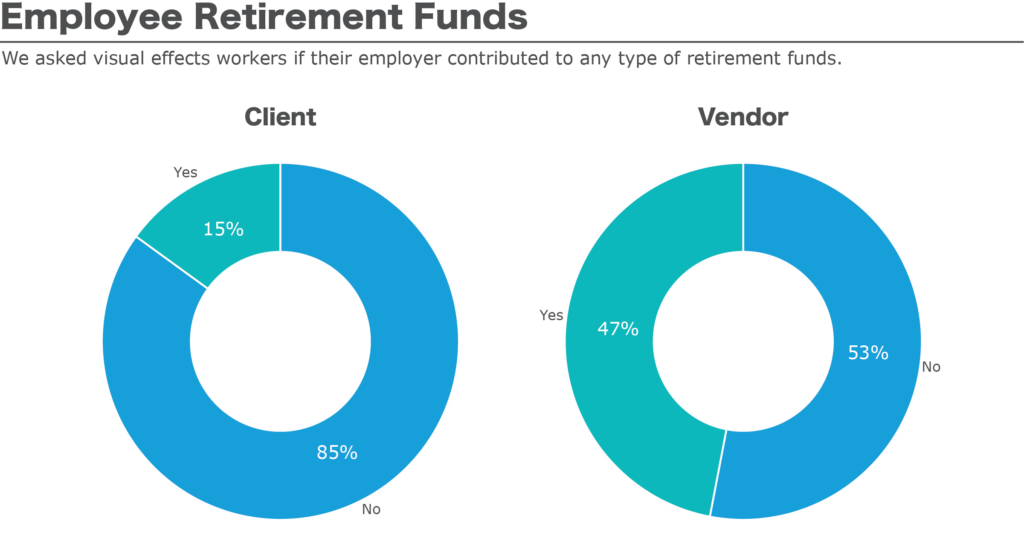

Retirement Contributions

As we saw with healthcare, the lack of employer-provided retirement benefits (a core component of IATSE-negotiated agreements covering our co-workers) is apparent throughout the entire VFX industry, but particularly on the client-side. An overwhelming 85% of client-side VFX crews indicated they lacked any employer-funded retirement benefits, as well as a majority of vendor-side workers (53%).

Considering VFX is no longer an industry in its infancy, but instead relies upon the experience and knowledge of thousands of workers who’ve made a lifetime career in this field, the lack of any widespread retirement benefits contributes to the mental and physical costs associated with our work. This puts workers at an extreme disadvantage when they retire because not only do they have less resources available to them, but they are responsible for all their retirement contributions on their own with no help from their employer(s).

Lack of overtime protection

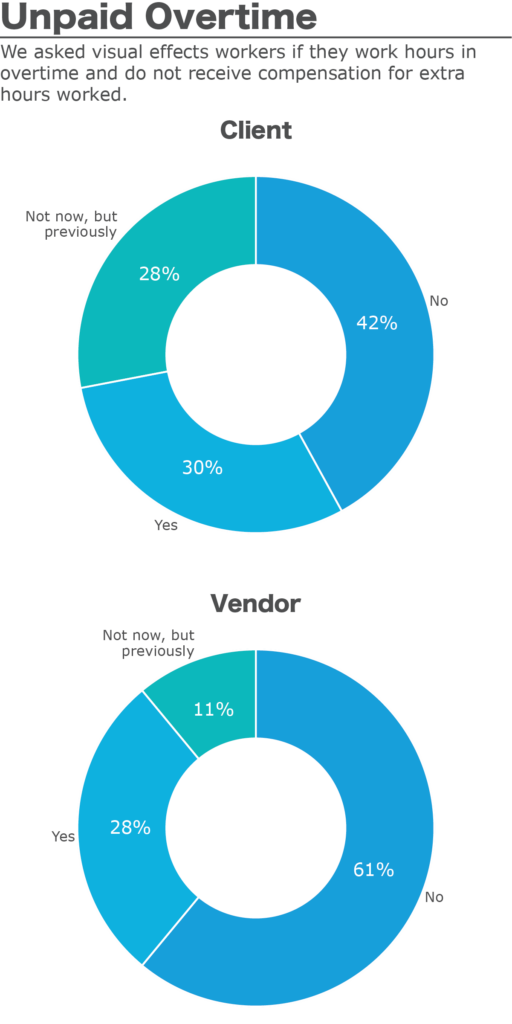

As discussed in the “Rates” section, there is widespread prevalence of unpaid overtime (wage theft) which has been reported by a majority of client-side crews, and a sizable proportion of vendor-side workers.

For the client-side, 58% of respondents indicated they had worked hours for their employer that they were not accurately compensated for. For some job titles, flat rate compensation has been so widespread and problematic that experienced workers are using the extreme demand for our labor to increase leverage in negotiations and secure hourly pay with overtime guarantees; Lead Data Wranglers, On-Set Supervisors, and VFX Production Artists are leading the way on this front. As an example, a Data Wrangler working for a flat-rate would be assumed to be working 12 hours-per-day; as any film crew worker could tell you, 12 hours is a standard shoot length which is not inclusive of the hours of pre-call and post-wrap work we are expected to complete each day in addition to our duties during the shooting call. The majority of client-side workers, without the benefit of wage transparency or a standardized contract, are forced to take a weekly flat-rate deal which virtually guarantees they will be working for free at some point almost every single day, potentially in violation of the overtime protections in the Fair Labor Standards Act.

As previously indicated when discussing rates, vendor-side workers typically see slightly better protections from wage theft, though 39% still indicated they had worked hours for their employer without compensation. Our analysis indicates this is mostly due to some job titles, especially for workers in artistic roles, having hourly pay with overtime guarantees. Vendor-side production workers (coordinators, production managers, assistants) reflect higher levels of weekly flat rate pay, which corresponds with higher reporting of wage theft.

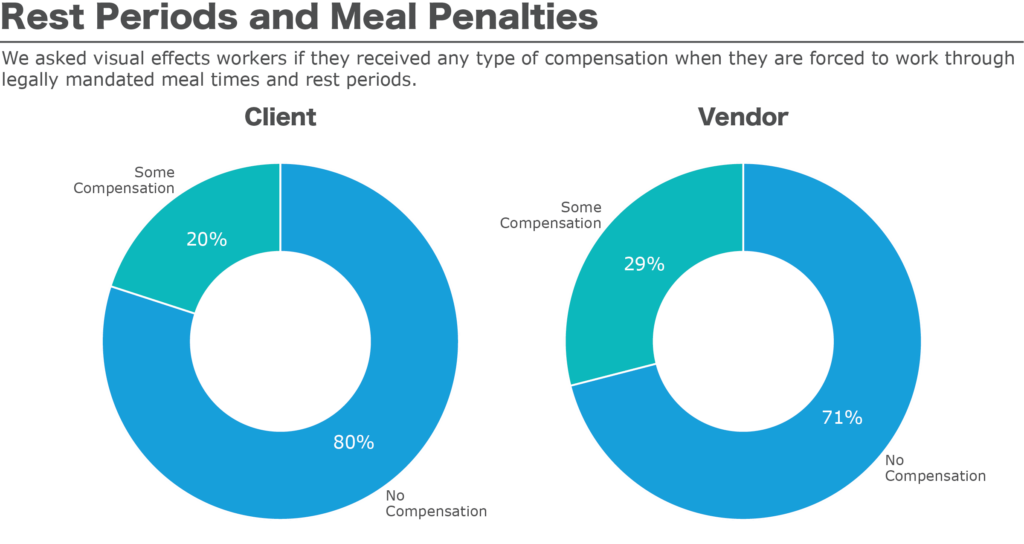

No lunch and no break

As part of our attempt to capture a snapshot of the working conditions of VFX crews and how they compare to their co-workers and other private-sector employees, we asked whether workers received what are known as “meal penalties”, which are payments mandated by most collective bargaining agreements in entertainment work given to workers when they are (as is often the case) forced to work through contractually-mandated meal break times and rest periods. Over 80% of client-side workers said they received no compensation for being forced to work through mandated break periods, and over 71% of vendor-side workers indicated the same.

As with unpaid overtime, this amounts to wage theft, but also contributes to the structural challenges that VFX workers face, as they cannot even depend upon the basic protections under the law (Division of Fair Labor Standards Act and Child Labor) which carve out periods for workers to rest, replenish their energy, and continue to operate efficiently and safely over the course of 12-15 hour days, often 6 or 7 days a week, for months on end. VFX workers on set are often told to use the lunch hour to capture set data and photograph props while the rest of the crew is breaking, and in post the norm is to eat lunch at your desk while processing paperwork. Film crew workers on set and in post are given catered or take-out meals due to their inability to walk away to find food for themselves, but VFX crews often have to struggle to find time to order and pay for our own food, which contributes to a culture of overwork where asking to take 30 minutes for lunch can be seen as a grave overreach by some producers or filmmakers.

Safety concerns in the workplace

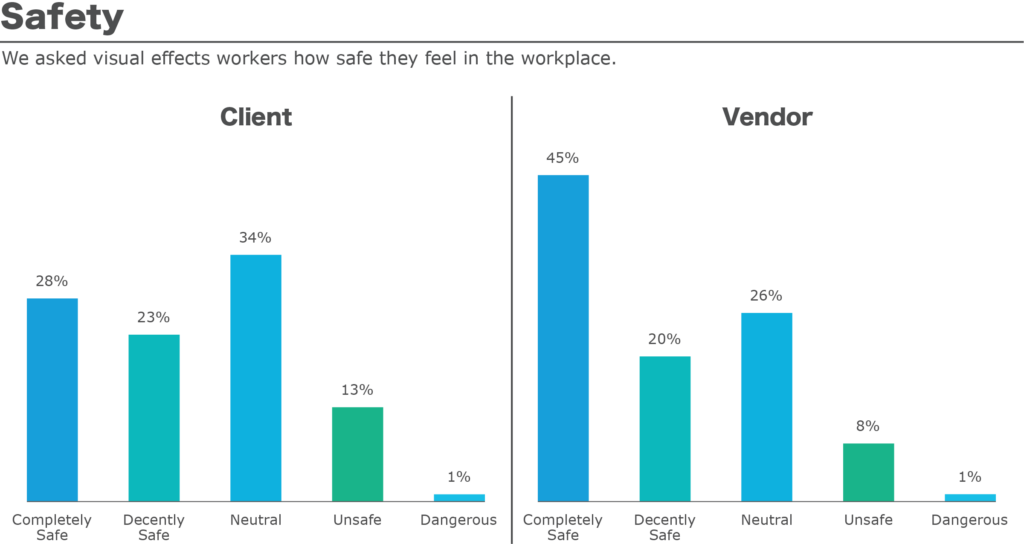

One of the chief reasons we have broken down this data set into the client- and vendor-side workers is to call attention to the fact that, in addition to the workers housed in vendor shops, there are currently hundreds of VFX crews working on sets across the world, who lack the basic safety and training regulations which the other crafts can rely upon to ensure workers feel safe on the job. We asked workers to rate their level of safety on a scale of 1-5, where 1 = workers lives in jeopardy, and 5 = workers are completely secure and protected.

As we expected, client-side VFX workers who work with the shooting crews indicated far greater safety concerns, with the majority rating their safety at a 3, reflective of the lack of union-enforced safety standards for these employees. VFX workers on set are often tasked with capturing difficult and dangerous elements, such as explosions, stunts, and splinter-unit duties which can put them at higher-risk than other departments. Additionally, without the benefit of a union hotline or field agent to enforce safe conditions, these workers often have no recourse for lodging their complaints with anyone besides the producers who may have ordered them into those conditions in the first place. This contributes to a culture of silence, as workers don’t want to be seen as “difficult,” since every future job opportunity is based on personal relationships with those very producers.

Vendor-side workers generally feel safer at the job, with the majority rating their safety as a “5”, but the next-highest response was a 3, indicating the significant concerns that many vendor-side workers feel about their protection. Based on the short-form responses we received, many of these concerns are the same experienced by client-side workers engaged in post-production, which center on the extreme stress, long hours, lack of healthcare or other benefits, and perceived inability to file grievances when appropriate, which can contribute to unsafe conditions which may percolate until they result in tragedy – many workers tell stories of falling asleep at the wheel after weeks of near-constant work, chronic mental and physical health issues, or of pressures to keep silent about abuses and violations they witness or are subjected to on the job.

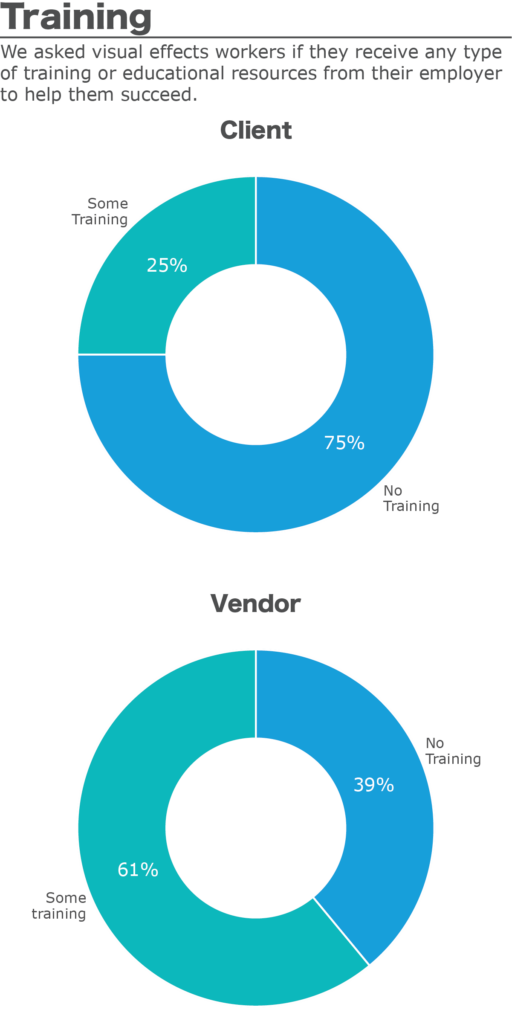

Lack of training

Going hand-in-hand with VFX workers’ safety concerns is the lack of VFX-specific resources provided by employers to properly train and certify employees for their responsibilities. Again, the distinction between client-side workers on a film crew and vendor-side workers at an established VFX house is apparent.

For client-side VFX workers, only 25% indicated the availability of any training or educational resources for themselves or their coworkers. Considering the extremely high demand for VFX crews currently, this has the effect in practice of ensuring that the crew members with previous experience will spend a significant portion of their time training newly-hired, or “green,” VFX workers while also completing their own job duties. Every director, studio, and producer has different workflows and expectations, and the lack of standardization across our industry means that workers often must become experts essentially overnight in entirely new software packages, photographic capture tools, filmmaking workflows, and more depending on the preferences of their employers. Client-side workers often complain of having to “reinvent the wheel” on each new production, whereas organized departments like Editorial or Camera have a standard set of procedures and tools (coupled with educational training programs) which allow them to come to work ready to get the job done. This is one more structural hurdle that VFX workers must clear in order to work in a sane and sustainable manner.

Vendor-side workers report much higher levels of training availability, but 39% still lack any resources for VFX-specific training or education. Since these are often longer-term employees housed in a more traditional workplace environment, and many artists come from an educational background focusing particularly on VFX or digital art, there are typically more clearly-defined standards for software, hardware, and job workflows. However, survey respondents report these companies are also notorious for their reticence to promote internally, with many vendor workers jumping back-and-forth between VFX companies in order to negotiate promotions or wage increases, and workers find the onus is put on them to become proficient in newly developed software and workflows. According to testimonies provided in this survey, those seeking to move up within a company are often told to take on additional, unpaid responsibilities – “doing it for your reel” or “working for the credit” – in an attempt to demonstrate their proficiency and dedication.

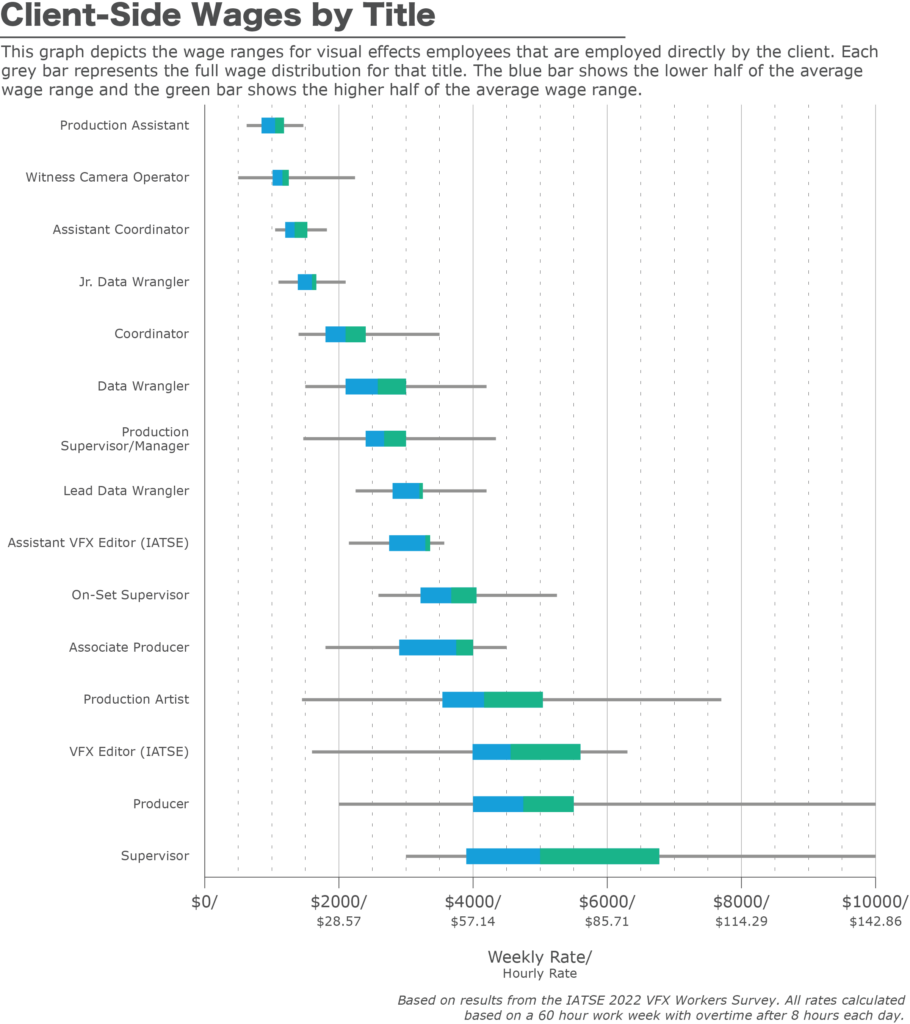

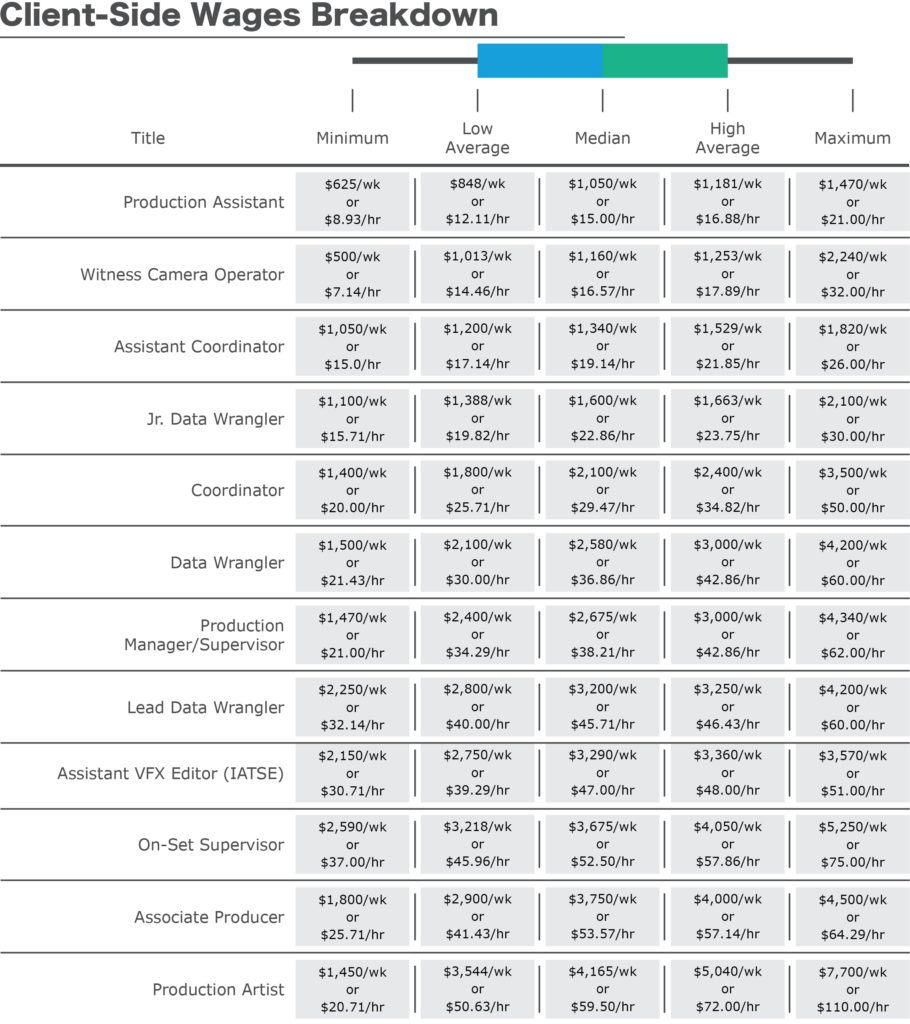

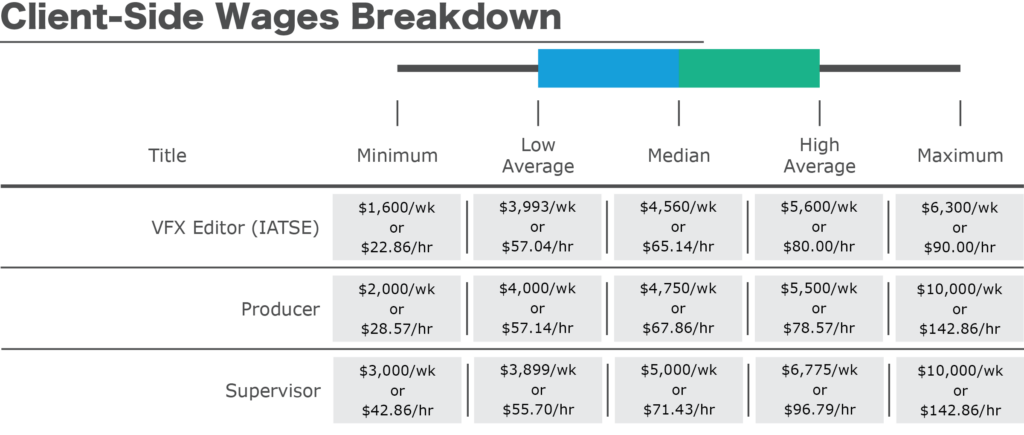

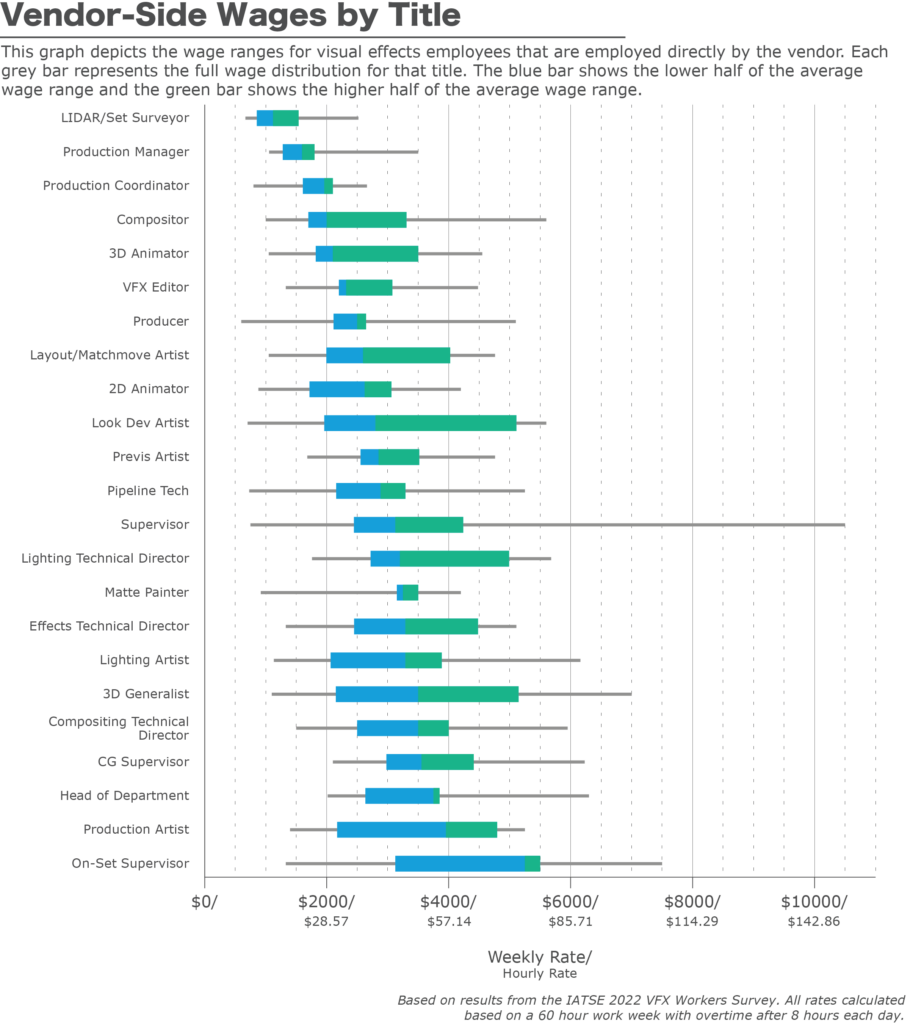

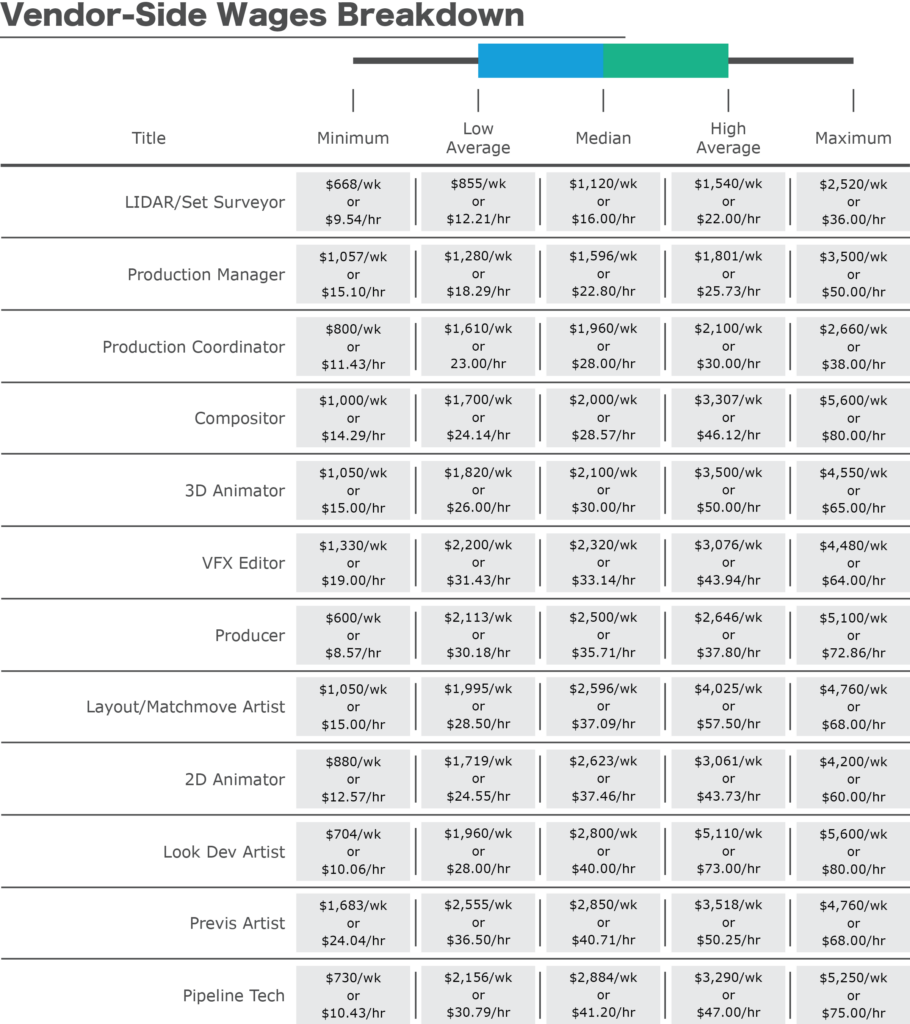

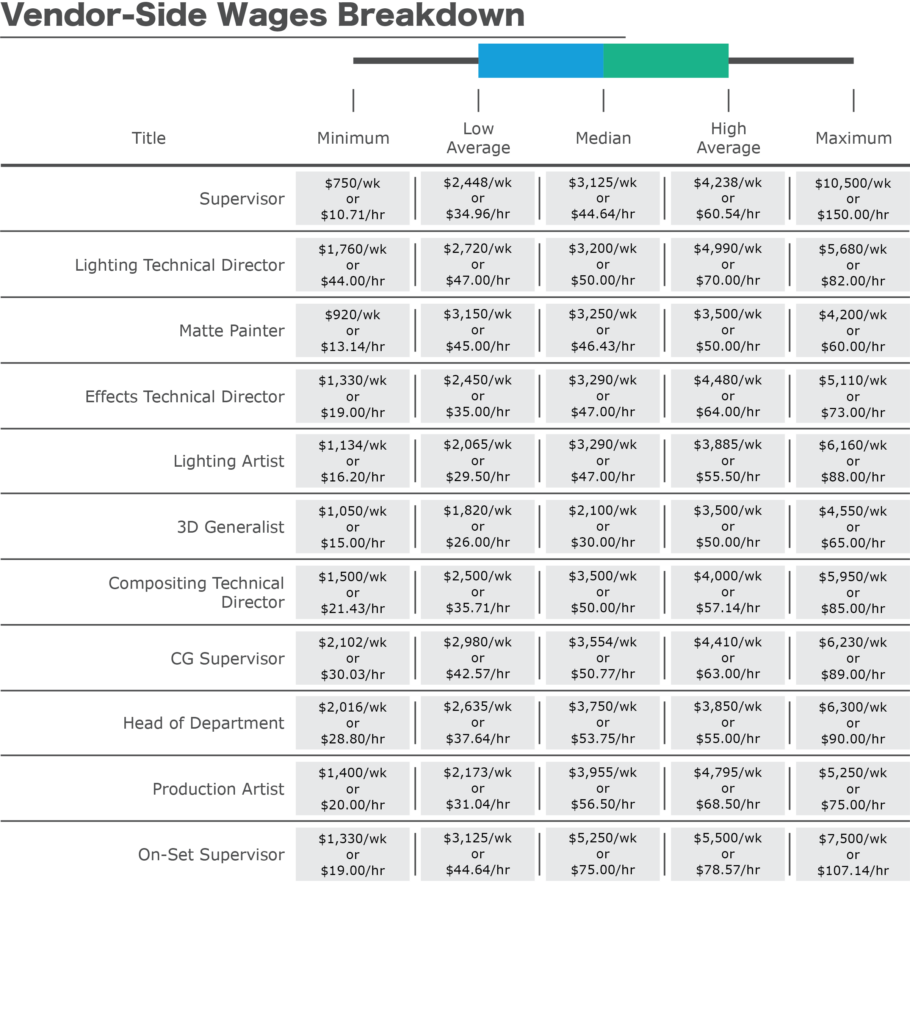

Current industry wage distribution

For all rates, we are presenting a minimum and maximum value submitted, as well as averages broken down into quartiles. This is a reflection of what workers self-reported as their weekly “flat” rates (typical of client-side VFX crews and vendor-side production workers) or hourly rates (usually the artists working at vendors). The client-side flat rates are calculated, according to the studios, to account for a 60-hour work week over 5 days, which includes 20 hours of overtime built-in; as our later data point on “Unpaid Overtime” (i.e. wage theft) demonstrates, the majority of client-side workers find their actual overtime far exceeds this assumption. For vendor-side workers who are paid hourly, for the sake of comparison we also calculated this rate based on a 5-day, 60-hour work week; the data we received shows that typically these hourly employees report lower rates of unpaid overtime, so we feel confident that these assumptions are useful in estimating an average week’s work.

Important takeaways from this section are that there are no minimum standard rates set across job titles on either the client- or vendor-side, resulting in a wide variation which is reflective of the lack of transparency that currently exists about how much workers can demand for their time. Additionally, while it may seem that client-side workers generally command higher rates than the vendor-side workers, they also lack the relative stability and even marginal benefits that can come from being employed by a large company, and typically have to factor in weeks or months of annual unemployment when they wrap off a project. We also see that, even on the client-side, job titles like Witness Camera Operator, VFX Production Assistant, and Jr. Data Wranglers have rates which can amount to minimum wage or less (when considering unpaid overtime).

Are visual effects jobs sustainable?

A more subjective question, we asked visual effects workers is whether or not they felt that VFX work was sustainable for them in the long-term. In this case, the distinction between vendor-side and client-side VFX workers was almost entirely negligible. 67% of client-side and 68% of vendor-side employees answered that they did not feel that VFX work, as it currently exists, was sustainable for them in the long term.

When we consider the fact that every major studio currently depends upon big-budget, VFX-heavy features, television, and streaming productions in order to maintain their bottom line, whether measured by box office returns or subscriber numbers; and the fact that there are more VFX crew job openings available than there are workers to fill them, this high level of uncertainty about VFX workers’ long-term ability to continue in their jobs should give everyone working in entertainment reason for concern. Whether on the client-side or the vendor-side, these workers have been generating billions of dollars annually for the studios with their labor, but as we’ve seen in the other survey results, the structural conditions which prevail for VFX employees contribute to overwhelming rates of burnout.

To that end, we further asked workers to identify their top priorities for improvement or change that would make their work in VFX more sustainable. Almost every worker had multiple top priorities, reflecting the urgency they felt in seeking to address these issues, but overall the most frequent responses were:

- Respect / A voice on the job

- Healthcare

- Pension

- Fair Wages

- Work Life Balance, including Reasonable Hours / Turnaround Restrictions

- Paid Overtime / End to Wage Theft

- Job Descriptions/Training

It has long been recognized that film workers’ project-based employment creates a “permalance” culture of boom-and-bust based on short-term projects with uncertain employment in between. The fact is that each of the priorities listed above has been previously addressed in collective bargaining agreements negotiated for the crafts that work alongside VFX at every step of the production process, and those agreements help unionized workers confront the broad power dynamics that will continue to exist within entertainment. Producers and studios will always want work that is better, cheaper, and faster than workers can reasonably provide, but without a voice on the job to push back and create boundaries and respect for VFX workers, this work will continue to be unsustainable in the long term.

What is the solution?

In considering the points challenging VFX workers and their priorities for change, we must ask the question: what is to be done? To that end, we asked workers whether they felt that, as individual workers, they had the ability to negotiate viable solutions to these priorities for change. Our final data point again presents almost no significant distinction between the client- and vendor-side workers.

Nearly nine out of every ten workers throughout the Visual Effects industry felt they had no way as individuals to negotiate for viable solutions to the issues identified in this report, comprising 88% of client-side workers and 87% of vendor-side workers. The overwhelming majority of workers feel that they either have no ability to negotiate better conditions for themselves, or have to depend on the personality of individual producers or the culture of their particular company to be able to gain incremental improvements.

When we also consider the finding that nearly 70% of VFX workers who responded felt their work is not sustainable long-term, the crisis facing these workers comes into focus. Workers in Visual Effects have long felt that the structural conditions of their labor, currently determined by their employers without input from the workers themselves, have fostered unfair practices and created a sense of VFX workers being “second-class citizens” who are unjustly excluded from the protections and benefits that their coworkers depend on. The data from this survey show that their concerns are merited, and suggest that only through collective bargaining can these shared priorities be comprehensively addressed.

Key Survey Quotes

“I’ve been around long enough and have advanced far enough that I feel I am at least well paid, so I feel that I can continue to do this work over the next 5-10 years. However the entire department would greatly benefit from unionization, especially those folks who are just getting started. Also, I have 20+ years in this job and don’t have a nickel of retirement to show for it.”

“I do not feel like it is sustainable. The lack of union backing has made my team’s ability to function properly inadequate. Lack of meal penalties for one. Morale is of great importance, and how we are treated as “less than” really takes a toll.”

“Constant contract work means not getting benefits like employer funded retirement savings. This becomes more of an issue as I get older. Many facilities provide these benefits only for staff not for contractors which are the majority of employees. In Canada healthcare is less of an issue as core services are government provided but extended benefits are still important and vary from facility to facility.”

“I can’t fathom any future where I can retire.”

“No, because at this rate the balance between cost/reward of the job is quickly spiraling out of control. Things like stress, depression, and burnout have become built-in aspects of the job.”

“I have been in and out of VFX since 1989. One reason I pursued the more sustainable route of cinematographer was that VFX has never been unionized or organized to any degree.”

“Not under these conditions, only because my health (both physical and mental) has been so negatively impacted from the low morale and hours we’re forced to work to make near impossible deadlines. Having to find new doctors for new ailments that crop up from the job while simultaneously staying at the job to pay for those doctors is a catch-22 I never anticipated.”

“Possibly, but only if there are a few major changes. Most importantly, health insurance needs to be made available on a more permanent (i.e. not job-by-job basis). Having a union to help regulate practices would also be a huge benefit.”

“No. Every time we do crunch my health declines. I can’t see myself doing this for more than five more years.”

What is your top priority for what you would want to see improved or changed to make work in VFX more sustainable for you and your co-workers?

“Better working hours and less crunch.”

“Availability of health insurance”

“Proper hourly compensation, qualified leadership, heightening morale, compensation for personal time having to be used to learn how to program when you got hired to draw, it’d also be nice to not be reprimanded for doing poorly on a task you’re not qualified for/isn’t your department”

“More stable project planning from directors and/or clients in order to cut down on revisions and stressful deadlines. More stable jobs instead of “mercenary” contracts.”

“Overtime pay, pension, health insurance. 401k”

“Lifetime/retirement career path, real vacation time, gaps between crunch projects”

“More staff roles, fewer contracts. Or provide the same benefits to contractors as staff. More push back on overly demanding client changes late in production.”

“To be treated like any other department.”

“Unionization of on-set (to start) VFX workers immediately.”

Glossary

Visual Effects – Any change to the photography of a film or television show after it has been shot is considered a “Visual Effect.” Practical elements which are generated on set to be captured by the cameras during regular photography are “Special Effects” (SPFX), a separate department which is represented by IATSE, but also shares the Academy Award for Visual Effects with the VFX department supervisors. VFX crews are often the first to be hired once a project goes into production and the last to be working on a show in post. Though most in the public do not realize it, these crews work on location as part of the shooting crew, capturing key data and collaborating with the filmmakers to successfully execute a final vision as laid out by the director. They pass this information and direction to visual effects companies (such as ILM, MPC, Digital Domain, etc.) and work with the teams of artists to develop the final look of the film.

CGI – “Computer Generated Imagery,” the most prevalent form of modern-day visual effects (though technically, optical effects, double-exposures, and other classic techniques of manipulating photography are also considered visual effects). Traditionally, CGI has been added to the set photography in post-production, but innovations such as the LED Volume Wall and “animatics” (animated storyboards) mean that CG now is incorporated into pre-production and production as well.

Client-side – the workers employed directly by a film production company, who work alongside the camera, art, editorial, and other IATSE-represented departments

Vendor-side – the workers who are employed by one of hundreds of visual effects production houses across the world, who are contracted by the studios to complete the artistic visual effects work for a project

VFX Supervisor – the creative head of the department, responsible for translating the director’s vision into instructions for teams of artists to complete the final artistic vision for a film’s visual effects

VFX Producer – the financial head of the department, responsible for hiring and firing crew, establishing production workflows, working with the studio and film’s producers to develop a budget, sending out bids for the work required, and contracting VFX houses to complete the work.

VFX Production Manager/Coordinator – Often called the “backbone” of the department, these workers keep track of the overwhelming amount of data captured on set or in creative reviews with the filmmakers, transmit clear information about approvals or revisions of work, coordinate with the other departments in sharing and receiving key information for shooting and post, and are sometimes called “Swiss Army Knives” because they are on call almost 24/7 for any other tasks or responsibilities that come up.

Data Wrangler – Data Wranglers, as the name implies, are responsible for capturing and collating an immense amount of on-set data in order to ensure the artists have enough information and context to replicate the lighting, lens, film stock, and other conditions that existed during photography in their CG workflows to create a seamless transition from practical to visual imagery. They work alongside the Camera department and record detailed information for every single take, as well as capturing high-fidelity images of props, costumes, makeup, sets, and anything else that might be required to be manipulated in post-production.

Witness Camera Operator – These workers are responsible for operating “witness cameras” on set, which are typically set up around the filming location with full coverage in order to provide context for particularly challenging scenes, usually involving intended-CG characters whose movements are important to keep track of beyond what is apparent through the photography captured by the film cameras.

Virtual Production Manager – These workers specialize in workflows involving mixed CG and practical elements, as with the LED walls that more productions are turning to as a replacement for traditional greenscreen, as well as virtual viewfinder workflows which allow camera operators on-set to see CG elements in-camera by routing image data through a 3D animation program such as Unreal Engine. This is a highly technical position requiring familiarity with a range of tools and knowledge sets, and works closely with the VFX Supervisor, Camera team, and Assistant Directors to ensure the shooting crew succeeds in capturing these elements.

On-Set Supervisor – Since the VFX Supervisor typically has a background as an artist at one of the VFX vendors before going freelance and working on-set with the client-side workers, and because the complexity and scope of responsibilities for VFX workers on-set has ballooned in recent years, On-Set Supervisors are often hired to direct the Data Wranglers, Witness Camera Operators, LiDAR/survey teams, and on-set coordinators in the performance of their job duties. They may also work with the VFX Supervisor, VFX Producer, and other departments to develop and execute a methodology for the shoot, ensuring that data and elements are captured as needed and allowing the overall VFX Supervisor to focus on iterating the final artistic look of the film.

VFX Production Artist / “In-House Artist” – While the majority of CG work is done at the vendor houses, some productions also hire individual or small teams of “In-House” production artists. These highly-skilled artists work under the direction of the VFX Supervisor to do a huge range of tasks which may be more efficiently handled locally rather than by hiring an external vendor; this can range from previs, postvis, temp effects, and cleanup; to major fixes needed on short notice; to completing full-CG shots for the final feature.

Vendor Positions – Many job titles (Supervisor, Producer, Coordinator, Production Manager, etc) are the same on the client and vendor side, with similar responsibilities. Below are some unique vendor positions.

Compositor – A sizable percentage of vendor-side artists are working as compositors, which often comprises the biggest department within the VFX vendor companies. These workers integrate the CG elements being added into the “plate” (original photography), using artistic and technical skills and the data captured by the on-set team to create a seamless blend between real and generated imagery.

Layout/Matchmove – Another very large sector of the vendor workforce, these workers “prep” the plates by generating spatial data about the environment captured by the cameras, blocking the CG elements which the compositors will ultimately be integrating, and tracking the movement of actors and elements inside the frame to allow any added elements to appear to be in the same environment as that which existed on-set.

Lookdev – the “R&D” branch of vendor operations, these workers experiment and iterate on various artistic and technical solutions to problems presented by the work requested by filmmakers. This can include characters, environments, elements, simulations, and any other visual effect which needs to have a unique look or approach.

Previs / Postvis – sometimes called “animatics” or “virtual storyboards”, pre-visualization is intended to block out the intended action which will be happening on set, and often shows the interaction between real and proposed CG elements. This is an artistic role which nonetheless demands highly technical skills, since details down to the lens used and precise distance between set elements or actors can have huge implications when attempting to recreate these shots on set. “Postvis” is a similar process but occurs after principal photography has wrapped, and allows editors and filmmakers to have a rough idea of the final look of the CG early in post-production, ensuring they can make editorial decisions which may otherwise have to wait months for the final CG to be completed.

Pipeline – These workers are vital to any vendor operation, as they oversee the processes and tools that are used to ingest photography and data from the client-side VFX team (often distributing multiple terabytes of data per day to each vendor), and allocate this material to the relevant production teams and artists in order to complete the work requested. They also pass back the completed shots to the client and are responsible for how data is shared within a vendor operation.

Works Cited

Division of Fair Labor Standards Act and Child Labor. “Minimum Length of Meal Period Required under State Law for Adult Employees in Private Sector 1.” U.S. Department of Labor, 1 January 2023, https://www.dol.gov/agencies/whd/state/meal-breaks. Accessed 19 February 2023.

Link to survey: https://vfxunion.org/2022-survey/

CONTACT AN ORGANIZER

* Submissions to this form are strictly confidential